Core genes have surprisingly high recombination rates

an explainer on the variation of recombination rates across the bacterial pangenome

length: 6 minute read, training necessary: none

Goal

The goal of this blog post is to provide a quick explainer of my recent work in eLife with the Kussell group on recombination across the bacterial pangenome.

Background

What are core genes?

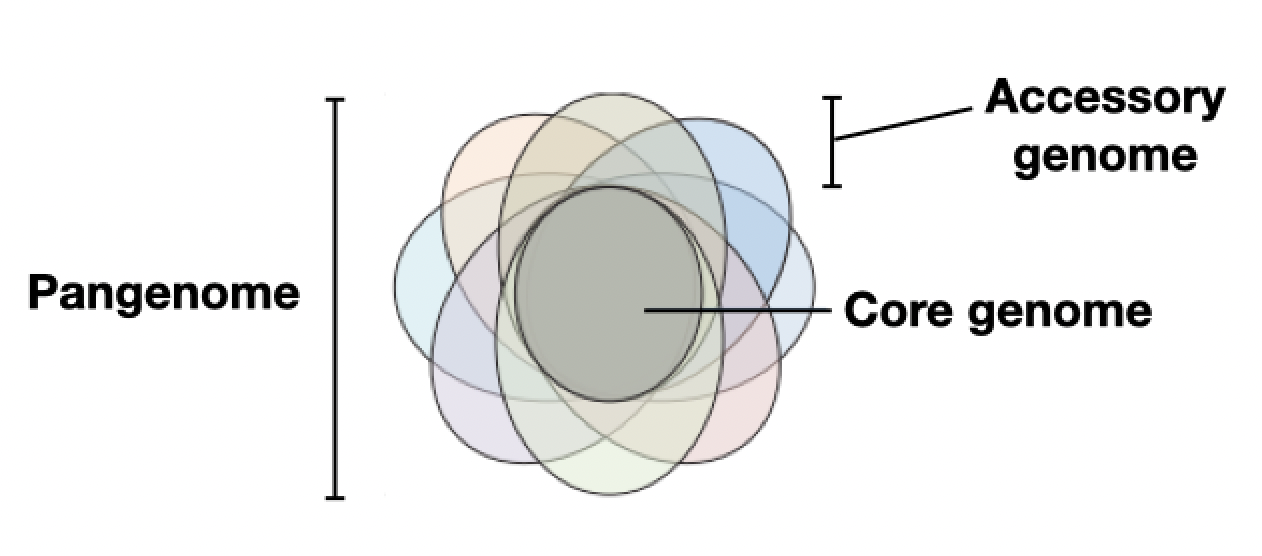

If you’re not a microbiologist, it may surprise you to learn that for each species of bacteria, there are different “strains” within that species. However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, nearly everyone is familiar with “variants”, which are more or less equivalent to strains. Strains are microorganisms that are the same species, yet are genetically distinct from one another. For example, the Delta and Omicron variants are two separate strains of SARS-CoV-2. Analogously here, uropathogenic E. coli (responsible for urinary tract infections) and E. coli used in the lab are different strains.

SARS-CoV-2 variants all have the same sets of genes, but there are substitutions

The core genome includes genes with essential functions, such as “housekeeping” genes which are required for maintenance of basic function. In contrast, the roles of many accessory genes are not understood. Some are thought to be adaptations in response to stresses that only show up in certain environments, which is why they’re thought to only occur in certain strains of microbes.

What is recombination?

In this paper, we specifically mean “homologous recombination”, or what has been more recently been referred to as “allele transfer”.

What we found

Largely because of the critical functions that many core genes have, the prevailing wisdom has been that core genes experience fewer recombination events (at least in the form of horizontal gene transfers).

- Virtually all previous methods to infer recombination rates have relied on re-building the phylogeny

You can think of a phylogeny as the entire evolutionary history of that gene. of each gene. Because accessory genes are rare, it’s tough to build phylogenies for them. - We previously lacked a computational method which could analyze the massive amounts of available whole genome sequences which exist for bacteria.

The Kussell group had previously developed a method that happened to circumvent these issues.

Core genes often recombine more than accessory genes.

This was a surprise, given how conserved these genes are. One might think that increased recombination in these regions could disrupt their vital functions.

What’s driving this behavior is a complex set of many factors. Based on our data, it appears to be in part related to what are called “divergence-based” recombination barriers.

Why should you care?

Good question! There are several implications. Here are a couple:

- These data suggests that “purifying selection”, an evolutionary force that acts to purge deleterious mutations, may be acting in concert with recombination to “homogenize” core genes. We think this may be because the functions of these genes are so critical, cells can’t afford to have many mutations in this part of the genome.

- This may require the field to re-think how we build phylogenies for bacterial genomes. Many have been calling for this already.

Core genes are frequently used for this purpose, and our data suggests that we likely need to properly account for recombination even when building phylogenies with core genes.

TL;DR version

For bacteria, genes which have essential functions often exchange more DNA than genes with non-essential functions.